Proust's Housekeeper

Céleste Albaret invites us to share in the delight that a person like Marcel Proust, for all his strangeness, ever walked among us.

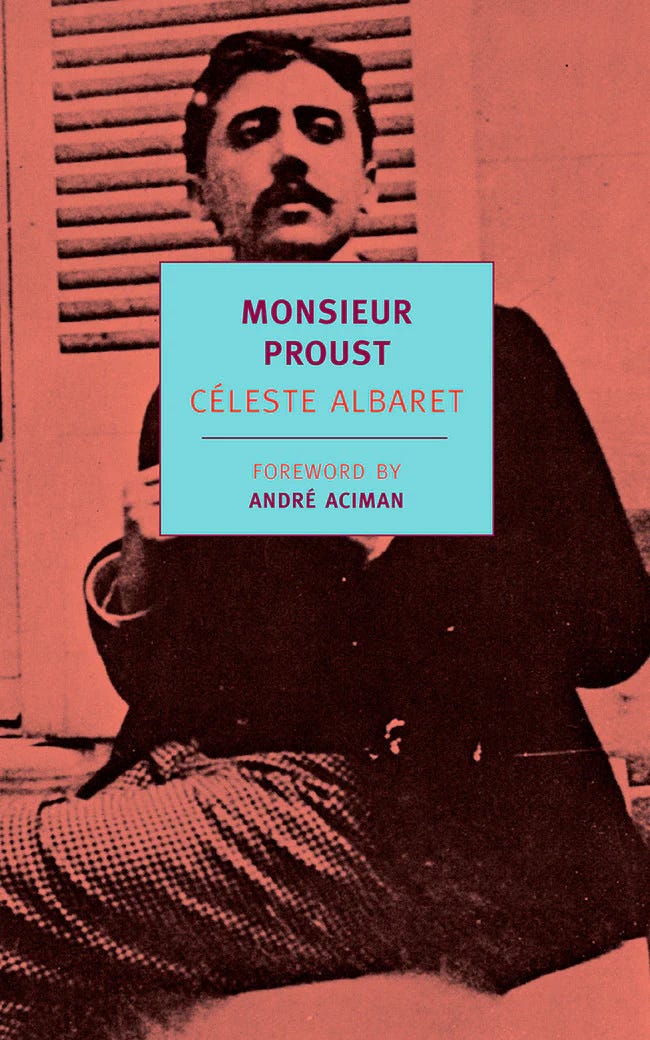

Céleste Albaret (2003). Monsieur Proust. New York Review of Books. (Foreword by André Aciman, translated from the French by Barbara Bray.)

Monsieur Proust is a remarkable socio-historical and literary document, offering a remarkably unvarnished account of a great literary personality’s everyday life. Anyone who cares about Marcel Proust’s writings should read Céleste Albaret’s gripping account of her years as his housekeeper. The book captures Proust’s peculiar, if not outright bizarre, life in Paris around the time of the Great War—which was also, of course, a time of frenzied creative activity, resulting in his monumental work, À la recherche du temps perdu.

But how could a book about the daily life of a writer’s housekeeper be gripping—even a very great writer and even an extraordinarily observant housekeeper? And yet gripping Monsieur Proust is. We follow both characters—for that is what they become in Albaret’s deft prose—along their varied stages of evolution, synthesis, and (spoiler alert) eventual disunion.

One quickly senses just how disturbed Proust’s interior life must have been: his irritation with every minor noise, whether from the neighbors or from Albaret’s own domestic work, his annoyance over his daily (nightly) coffee being insufficiently hot, and so on. Albaret notes that Proust had the uncanny ability to do without everyone—everyone except her, that is. He didn’t need anyone, it seemed to her, even if lots of people thought they were his friend, perhaps his most “inhuman” quality: “[H]e could do without all of them with the greatest of ease” (p. 223). But his unsociability, a kind of post-human quality, was in service of a deeply humanistic literary project: “Now I realize M. Proust's whole object, his whole great sacrifice for his work was to set himself outside time in order to rediscover it. When there is no more time, there is silence. He needed that silence in order to hear only the voices he wanted to hear, the voices that are in his books” (p. 50).

Albaret doesn’t gloss over Proust’s despotism nor does she completely forgive Proust’s prickly-pear qualities for serving the higher function of Art. Instead, Albaret is a subtle dialectician who realizes the fullness of her biographical subject, with all its multivalences, approaching what the French philosopher Gilles Deleuze would call “a life”: a life is just a life, to be described and accounted for, not destroyed—for it is up to us to make something out of every life we have a chance to learn about.

Proust was, famously, neurotic verging on the extreme. His own explanation for this was was that being a the son of a doctor, a certain hypochondria was unavoidable. “When you are a doctor's son, you see, you end up being a doctor yourself” (p. 60)—surely one of the great sociological defenses of neuroticism.

He was a nocturnal creature, going to bed in his cork-lined room at sunrise and rising only with the dusk. His physical needs seemed limited: “It isn't an exaggeration to say he ate virtually nothing,” Albaret writes, of what we today would probably describe as an eating disorder. “I’ve never heard of anyone else living off two bowls of café au lait and two croissants a day. And sometimes only one croissant!”. But Albaret doesn’t shy away from a brutally honest catalogue of his tyrannies, major and minor; still, we get the sense that there existed a profound bond of love between them, and she became far more than a domestic servant to him.

Above all, there is a tremendous sense of decency, even decorum, throughout her account, but also a genuine, authentic love: almost a divine love, totally innocent. At first an inexperienced young woman from the countryside, recently moved to the bustling metropolis of Paris, Albaret had to be taught everything about housekeeping, Albaret later becomes something like a maternal surrogate to Proust: “What was so marvelous was that with him there were moments when I felt I was his mother, and others when I felt I was his child” (p. 90). There’s plenty to be aggravated about here, of course, but, importantly, Albaret herself largely isn’t. Instead, she seems grateful to have played a not-inconsiderable part in the life of her beloved “Monsieur Proust,” delighting in his books, their reception, and his standing in literary history.

So was Albaret just a victim of ideology—the beliefs about masters and servants obtaining in a fin-de-siècle European society and stretching into the interwar years, where servitude and domination were sentimentalized, and servants were enjoined to love their masters, all for the purposes of securing consent to social domination? The ironclad hierarchies of class and privilege hang over nearly every page of Monsieur Proust; but this seems almost too obvious to mention, and what is remarkable is that Albaret—who by the time she came to write her memoirs was looking back on her youthful labors from the perspective of old age and considerable experience—doesn’t seem at all troubled by the brute facts of class and gender so vividly on display in these pages.

Instead, one gets the sense that, in the end, she took more from Proust than he took from her. His was an extraordinary tutelage, it seems, and Céleste Albaret invites us to share in her gratitude that such a strange, disorienting, sensitive, and extraordinary personality ever walked among us.

TheoryBrief Links

Thank you for reading The Theory Brief. Here are some of the things we’re watching, reading, and thinking about this week:

•Wall Street Journal: The Drugs Young Bankers Use to Get Through the Day—and Night

These days, drugs are more a tool to optimize performance on the job. Especially for entry-level bankers at the analyst and associate level—who work long, tedious hours and fiercely compete for higher-level jobs with big pay days—prescriptions for stimulants such as Adderall and other ADHD drugs have become commonplace.

•Chartbook by Adam Tooze: Chartbook Reissue: Reading Grossman's "Stalingrad" and "Life and Fate"

Grossman’s totalitarianism is not that of 1950s liberals in the West, nor is it that of Hannah Arendt. For Grossman, totalitarianism is, of course, characterized by coercion and the deprivation of freedom, but what he focuses on is the dynamic of power mobilization and production.

•Bloomberg: Biden Cancels Nearly $4.3 Billion in Public Worker Student Debt

The move — which represents the cancellation of $4.28 billion owed on federal loans — pushes the total number of individuals who have received relief under Biden administration programs to nearly 5 million, the White House said. In total, about $180 billion has been forgiven.

•The Guardian: Train conductor’s bilingual morning greeting raises hackles in Belgium

The use of both the Dutch and French greetings was not good enough for one Dutch-speaking passenger, who told him off, saying: “We’re not in Brussels yet, you have to use Dutch only!”

•Critical Inquiry: John Cayley reviews The Chinese Computer – Critical Inquiry

From this and the other axioms, Mullaney derives an overarching thesis, interpreting the inscriptional practices that emerged from Chinese computing as a phenomenon he christens hypography, “writing that operates in the service of conventional writing . . . at a register beneath” (p. 20).

•Wall Street Journal: Has World War III Already Begun?

Despite this escalation, the major powers are not fighting one another directly—at least not yet. “It’s not a world war by any stretch of imagination. It’s still a proxy war,” said Sen. James Risch, a Republican from Idaho, who is slated to become chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee next month.

•Aljazeera.com: EU research funds flow to Israel despite outrage over Gaza war

Fabrizio Sebastiani, director of research at the National Council for Research in Italy (CNR), has been using machine learning – a subset of artificial intelligence (AI) – to establish the authorship of unattributed medieval texts.

“While this topic might seem innocuous, I was horrified to learn that the very same machine learning techniques are also at the basis of the recently documented Lavender system” employed by the Israeli military for use in Gaza, he told Al Jazeera.

•Berggruen Institute/Youtube: Kojin Karatani: 2022 Berggruen Prize Laureate

•CNN: Apple urged to remove new AI feature after falsely summarizing news reports | CNN Business

The press freedom group Reporters Without Borders is urging Apple to remove its newly introduced artificial intelligence feature that summarizes news stories after it produced a false headline from the BBC.

The backlash comes after a push notification created by Apple Intelligence and sent to users last week falsely summarized a BBC report that Luigi Mangione, the suspect behind the killing of the UnitedHealthcare chief executive, had shot himself.

Books Spotlight

Books we’re enthusiastic about this week:

Tiziano Bonini and Emiliano Treré (2024). Algorithms of Resistance: The Everyday Fight against Platform Power. The MIT Press.

Drawing from rich ethnographic materials and perspectives from both the Global North and South, authors Tiziano Bonini and Emiliano Treré explore how people appropriate and reconfigure algorithms to pursue their objectives in three domains of everyday life: gig work, cultural industries, and politics. They reveal how forms of algorithmic agency and resistance are endemic and mundane and how the platform society is a contested battleground of contrasting forces.

Eric Storm (2024). Nationalism: A World History. Princeton University Press.

In Nationalism, historian Eric Storm sheds light on contemporary nationalist movements by exploring the global evolution of nationalism, beginning with the rise of the nation-state in the eighteenth century through the revival of nationalist ideas in the present day.